One year into my PhD exploring the sales life of contemporary trade non-fiction books and I still feel like I am just scratching the surface of my topic. So what is life as a researcher like? On a day-to-day basis I divide my time between:

- immersion in my subject area – reading journals articles and scholarly publication to keep up with innovations in the fields of publishing studies, literary studies, and the broader fields of cultural studies and digital humanities.

- writing – ranging from annotated bibliography entries, notes made at events, results and findings of my research and data analysis, or blog posts like this one. The important thing is to write often.

- wrangling sales data – using a combination of familiar tools and techniques such as vlookup in Excel, box plots in SPSS, or tools that are new to me such as big data analytics using python and weka.

- skills training – living half way between Glasgow and Edinburgh allows me to take advantage of many events organised within my own institution, University of Stirling, or the other institutions that make up the Scottish Graduate School of Arts and Humanities.

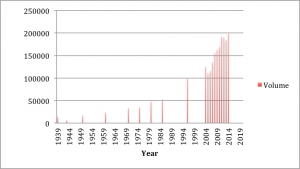

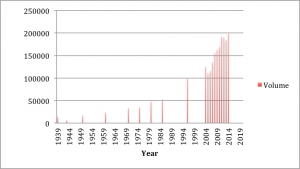

But why study the sales life of books at all? Well because the UK produces huge quantities of books. It has the highest per capita output in the world and the third highest number of new and revised titles published each year (behind China and the USA). This number of new and revised titles has risen steadily since the end of the Second World War from an almost standing start of 6,000 new titles in 1943 to over 200k in 2015.

Graph: Volume of New and Revised Titles Published in UK by Year

[Various Sources: Bookfacts, Nielsen BookScan, Publishers Association (2016)]

These statistics alone invite many questions: who is writing all these books? How many more people are involved in the design and refining of these products? How and why does the machinery of publishing manufacture and distribute at such a vast scale? However, my research is more interested in the next stages of the supply chain. What happens when these new titles are added to those already in print; the millions of titles which make up UK publishers’ back catalogues known as the backlist? How are all these books, both new and established, squeezed into bookshops (physical or otherwise)? How are they merchandised and sold? How long is the window of opportunity for them to succeed or fail? What does success look like in modern bookselling terms – and which authors and titles have achieved this? In the so-called age of abundance, which books have persistent sales and why?

My research objectives are ambitious (or so I’ve been told); to quantify the average sales life of non-fiction titles by subject category, identify longselling titles that have remained relevant to the UK book buying population over long time period, then explore the qualities, and cultural significance of some of these books via case studies.

An example of a longseller from one of the slowest selling bookshop categories, “Music and Dance”, is The Inner Game of Music by Timothy Gallwey and Barry Green. Originally published in 1986, this book is not the bestselling title in its class (that would be the BBC Proms Official Guide), but it is one of the few titles that appear in the top 5000 physical book sales charts for both 2001 and 2015.

Ranked 54th in the category of Music & Dance in 2001, it sold just under 2000 units and continued to rank in 312th position in 2015 with a modest 500 units sold in that year. Clearly, the sales for this title are declining, however three decades of bookshop sales is a noteworthy achievement and warrants a closer look.

Scrutinising the quantitative data alone provides some clues that The Inner Game of Music might be atypical for a book about music. It is certainly not a beginner’s guide to guitar, or piano, as are most of the other longselling titles within Music and Dance. However, the next step in the research journey is to explore the historical and commercial context for this book’s success and the opinions of its readership.

Initial investigation uncovers that the “inner game”, as a concept, was not originally developed for musicians. It is a spin-off from Gallwey’s NYT bestseller The Inner Game of Tennis, a book which teaches tennis players to improve their practice through awareness of psychological barriers, removal of self-doubt, and correction of bad habits. This philosophy is something Gallwey adapted and applied to other walks of life (golf, work, stress and music). He appears to have made a successful career out this brand through consultancy, public speaking and book sales. The Inner Game of Music also appears frequently on university reading lists, lending some academic weight to its commercial popularity.

This looks like a promising start for a case study, offering up a number of avenues for further research. How do readers discuss the book via online reviews? How is the book is positioned and sold within general and specialist bookshops; What is the impact of proactive and consistent marketing of the book by the author? Is self-improvement a common theme within longselling books?

All these questions demand answers, provoke my curiosity and spur me on to continue researching longselling books. And on that note, I guess I had better finish procrastinating via this blog article and get back to the PhD.

Helena Markou’s professional career spans publishing, bookselling and digital consultancy. Within her academic career she has lectured in Publishing at Oxford Brookes University and Digital Book History at the School of Advanced Studies, University of London. She is in her 2nd year of an AHRC funded PhD at University of Stirling. You can follow her online @helena_markou